Positive Impressions

When placed

against the situations presented for the ladies in the inset narratives, the

positivity seen in the data seems jarring. The unfortunate circumstances that

led these women to establish and join Millenium Hall could be seen as enough to

justify a melancholic outlook on life. As Mrs. Maynard translates these women's

stories to Lamont and Ellison, it is easy as a reader to sympathize with the

women of Millenium Hall. The important distinction, when you actually look at

the words on the page. Well as readers we might be attached to the sad melancholy

story, the women in Millenium Hall are much more willing to live in the present

rather than the past, as suggested by the use of the positive terms we see in

the text. Additionally, because this is a utopian model for women, it makes

sense that the women would be more focused on the present than on the past. The

circumstances of their past brought them to this place, something that likely

would not have been created without this background. These observations also seem to give insight into Sarah Scott's own outlook on life - perhaps that it is more important to value the things that have brought you to where you are, given you the opportunities you have and created the life you lead rather than to get stuck in a past that you had little to no control over. The women seem content with their present situations because they do have some autonomy and agency in their lives.

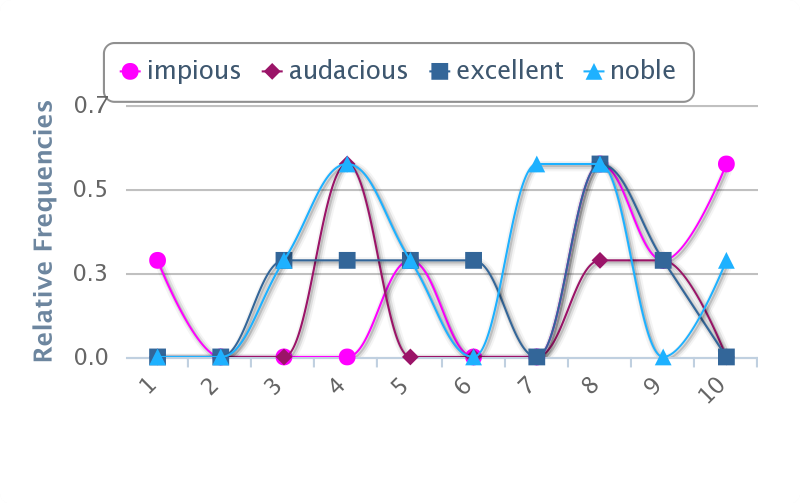

When I first

started reading the novel, I was surprised at the vastness of the positive

language within all of the hardships and heartbreak but I was not at the same

time. I amazed at the multitude of negative energy coming from the novel yet we

have all of these positive words. When you read the novel, you sympathize with

the ladies of Millenium Hall because you hear about their horrible pasts. Then

you start to root for them because they want to look to the future so you can

understand the use of the positive words to further the novel as a whole.

Rule of Law and Disobedience

Just as any good

utopia would, Millenium Hall lures you in with the promise of freedom and

happiness and white, fluffy clouds.

However just over halfway through, the laws and the rules are laid out

to the visitors and residents.

These rules are laid down all at once. After this, disobedience shows up. After all if there are no rules, there is nothing to

disobey. It is interesting that

the first mention of disobedience is right at the point at which rule and law

is the most heavily addressed.

After the enormous burst of rule and law, that talk subsides but

disobedience is still a factor and has another spike. The peculiar thought that this graph brings to my mind is

whether we can have a utopian novel at all without at least a hint of a developing

dystopia to offset the perceived perfection.

Work, Education and Gender Roles

Although Millenium Hall is written as a female

utopia, “man” is used 111 times while “woman” is only used 90 times. On the gender roles in the novel, it is

interesting that the words “man”, “woman” and “work” all begin relatively proportionate

and end at the same point. “Education”

and “work” seem to oppose each other at the beginning and end of the novel,

although they follow each other closely throughout. The interesting points to observe are at the beginning and

at the ending. This information

could make a profound statement about the novel as to what the ladies of

Millenium Hall have accomplished.

So at the beginning, we have “man” valued higher than “woman” as well as

“work” valued higher than “education.”

This is in the “man’s world” – the patriarchy. At the end of the novel, the effect of Millenium Hall seems

to be a close equality of “man” and “woman” while “work” and “education” have

managed to close the gap ever so slightly. It could be stated that this mirrors the conclusions drawn

by the men who have spent so much time visiting the Hall.

Conduct and Behaviour

According

to the OED, ‘behaviour’ is defined as “conduct, general practice, course of

life; course of action towards or to

others, treatment of others.” Conduct, then, is defined as “manner of

conducting oneself or one’s life.” So while the words share a similar meaning—the

way you act—there is a small nuance in that behaviour tends to be a more public

affair, and it tends to be short-term in the novel.

Behaviour

shows up most during the narrative of Mrs. Morgan’s and Miss Mancel’s lives—Lady

Melvyn’s behaviour towards her step-daughter, Mr. Hintman’s behaviour towards

Louisa, Sir Edward’s behaviour, and so on. Behaviour is always used to refer to

how they act towards other people: to engage their affections, to attempt to

dissuade them from said affections, or simply to try and make them hate someone

less (Lady Melvyn and Miss Melvyn). Conduct tends to be used to describe

someone’s long-term behaviour. Conduct also frequently shows up when someone is

reflecting back on how they’ve acted—Lady Mary reflects on her conduct rather

than on her behaviour, for example.

Despite

the amount of times these words show up—behaviour at 47 and conduct at 57—I

wouldn’t say the novel is overly concerned with instructing readers on how to

act. In large part the words show up in the inset narratives, during which time

the conduct of the ladies and of the people around them bring them close, but

never quite to ruin. So while the novel may be praising the good and

criticizing the bad, I wouldn’t say that it is trying to influence its audience.